On the Uses of Expertise

or

The Bartels–Frank Controversy Revisited

I published What’s the Matter With Kansas? in 2004 but here we are sixteen years later and the question that comes up most frequently about it has to do with the repeated criticisms of the book by political scientist Larry Bartels, formerly of Princeton University. Those who remember the matter always seem to regard Bartels’s opinions of the book as more authoritative or advanced than those of an ordinary reviewer because Bartels was an academic of high rank and because his opinions were expressed in the seemingly unimpeachable language of mathematics.

What I have also found over the years is that those who ask me about Bartels’s criticism are rarely aware of any of the rebuttals to it, written by me or by others. Indeed, it seems to surprise them to learn that one might contrive to rebut a math-based put-down at all.

Hence this page. The object here is to close the book on this long-ago debate by memorializing the basic points of contention. In what follows I will summarize the argument; give the facts that support my side of it; and pose the following question to anyone who still cares: What are the consequences when our most celebrated social critics embrace a reassuring political vision that is at odds with reality?

*

The dispute began with the publication of my 2004 book, What’s the Matter With Kansas?, which aimed to describe working-class conservatism as it appeared in an overwhelmingly white and distinctly non-Southern state. What led working people to sign up for a political movement that had little interest in the traditional economic concerns of the working class?, I asked. The conclusions I arrived at mainly had to do with the way populist rhetoric had been taken over by conservatives, especially via the culture wars (abortion, gun control, public education issues, etc). I also criticized the Democratic Party for losing sight of its populist roots and choosing, as I put it in the book, “to forget blue-collar voters and concentrate instead on recruiting affluent, white-collar professionals who are liberal on social issues.”

Larry Bartels, then a professor at Princeton University, launched his long-running attack on this book with a 2005 political science conference paper (it was much circulated on the Internet) in which he argued that white, working-class voters had not shifted Republican in a significant way outside of the South. (And hence, by implication, that it was pointless or wrongheaded to study blue-collar conservatism, as I did in Kansas.) At the time this was widely regarded as the most authoritative kind of scholarly finding, buttressed as it was with math and Ivy League prestige.

Since the elections of 2016 and 2020, however, the Bartels Thesis has largely disappeared from the venues where it was once respected and repeated. Instead, the commentary class has come around almost unanimously to the opposite point of view: that white, working-class people (often described as “non-college-educated whites”) have abandoned the Democratic Party in enormous numbers for the Republicans. Political journalists now frequently describe blue-collar whites as the “base” of the Republican Party, and GOP leaders often refer to their organization as a “worker’s party.” Indeed, this is now widely believed to be a global shift. It has been the subject of enormous commentary in Western Europe as well as in the U.S.A.

There were seven important stages of the Bartels-Frank controversy.

1. What Was it All About? Beginning in 2005, Larry Bartels attacked my Kansas book three different times: First, in a 2005 paper which he presented at the annual meeting of a political science professional association, then in a considerably revised academic paper published in 2006 in the Quarterly Journal of Political Science, and finally as a chapter in the first edition of his 2008 book, Unequal Democracy. There were revisions over the years, but his main argument, which we shall call the Bartels Thesis, remained roughly the same throughout. An article published in the Daily Princetonian in 2005 summarized it well:

According to Bartels’ results, the white working class has not become more conservative. Neither has it abandoned the Democratic Party. Over the past 30 years, the average views of working class whites have — according to Bartels — “remained virtually unchanged.” While the overall trend among white voters has been toward Republicanism, closer examination reveals that this has occurred amongst middle and upper-class voters, whereas the working class has actually become more reliably Democratic.

There was also a subtler argument lurking behind the main effort: an effort to wrest political commentary away from nonacademic writers. In that same story in the Daily Princetonian, for example, Bartels himself described his attack as an effort to push back against what he called “pundit literature,” presumably meaning commentary by unauthorized people like me. As we shall see, this theme would also be picked up and embraced by Bartels’s supporters: Academics, they would argue, held a monopoly on legitimate political discourse. The way to think about politics was by analyzing numbers from certain national data sets, or (alternately) by listening to academic experts who had experience analyzing those numbers.

The Bartels Thesis was much celebrated at the time. America’s leading liberal newspaper columnist wholeheartedly embraced it, as did the editor of America’s leading journal of the left. Bartels reprinted a version of his original article in Unequal Democracy (2008), a book that was then endorsed by former president Bill Clinton. President Barack Obama was also reported to have read the book. Bartels’s publisher referred to the book as an “instant classic.” Unequal Democracy won several prestigious political science awards.

I myself was surprised by Bartels’s attack when I first encountered it in 2005. The controversial aspects of Kansas, up to that point, had to do with my take on the culture wars. My observations about working-class Kansans enlisting in the conservative movement were familiar to anyone who lived in the state, and the theoretical framework I used to describe this shift was not new or daring. In fact, the rise of working-class conservatism had been one of the most-commented-upon developments in the period from roughly 1968 to 1980. Back then this development was widely thought to be the key factor behind the George Wallace campaign and the subsequent electoral successes of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

The literature on this subject was vast. For starters: Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority; Ben Wattenberg and Richard Scammon, The Real Majority; Michael Novak, The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics; Anthony Lukas, Common Ground; and perhaps most importantly, Jonathan Rieder, Canarsie: The Jews and Italians of Brooklyn Against Liberalism (read some reviews here). There was even a TV show on this famous topic: All in the Family.

(The increasing estrangement of the white working class from liberalism—the “heart of the Democratic Party’s New Deal coalition”—had also been one of the big political news stories of 1995.)

Bartels mentioned this stuff only in passing in his attacks on my book. He also said little about political events in Kansas, which was (after all) my immediate subject. Instead, he questioned the existence of white working-class conservatism, period. In Kansas I had described members of this cohort who were signing up for the Republican right and Bartels used national poll results to insist that such a thing was in fact not happening and that, outside of the South, white working-class voters remained staunchly Democratic.

Definitions were critical here. In his first and third efforts to prove his argument, Bartels defined “the working class” simply as the bottom third of the income distribution, and then—using data from the American National Election Studies or ANES—proceeded to point out that most of the people in the bottom third voted for Democrats.

2. I replied to Bartels in 2005, posting an essay (here it is, read it, it’s fun) on my website in which I argued that the eminent scholar missed what was happening because his definition of working class-ness was wrong. I also accused Bartels of overlooking evidence that contradicted his thesis. “The fundamental assumption animating Bartels’s attack on What’s the Matter With Kansas?,” I wrote, “is that studies like mine—based on movement literature, local history, interviews, state-level election results, and personal observation—are inherently inferior to mathematical extrapolations drawn from the National Election Surveys (NES). Indeed, Bartels seems to understand his assault on WMK as a blow struck for responsible academic professionalism against a contemptible ‘pundit literature.’ ”

Here is how my argument went:

- Bartels’s definition was wrong. Bartels defined the working class as people in the bottom third of the income distribution, but this definition included large numbers of other groups, such as young people just out of college, retired people, and the poor. He was also, incidentally, excluding many members of unions, whose working-class-ness is undeniable, but whose income is often closer to the national median.

- There were other ways of capturing working-classness using the tools provided by the ANES. These were not examined in detail by Bartels. When you used these other ways, however, the results were the opposite of what Bartels claimed. For example, the category that is most frequently used by pollsters and sociologists to capture social class is educational attainment, and when you define the white working class using this metric (i.e., non-college-educated whites), it became clear that white working-class voters went lopsidedly for the Republican candidate in the 2004 election, which was the most recent one at the time. When you define working-classness using voter self-description as “working class” (and, yes, this is also included in the ANES data), white working-class voters, again, could be seen going for the Republican in 2004.

- I also suggested that it was inappropriate to judge studies of working-class conservatism solely by reference to the ups and downs of national election results. Journalists and sociologists study the views of communities around the country and around the world—small towns in Iowa, say, or “white ethnics” in Boston—and national election results are not the criterion by which we ordinarily evaluate these studies.

“Conservatism has changed the face of America and of the world,” I concluded. “The changes it has wrought are largely irreversible. To respond to all this by just blowing it off—by asserting that it’s a waste of time to examine the populist conservative mindset—is folly on a magnitude that not even a political scientist can measure.”

In response to this essay, which I published solely on my own website, Bartels in 2006 wrote an academic journal article in which he modified his definition of “the working class” to include educational attainment but persisted with his original conclusion, i.e., that white blue-collar workers are reliable Democrats. He argued that the mystery of working-class conservatism was almost completely limited to the South.

Then, in his 2008 book Unequal Democracy, Bartels returned to his first definition—the bottom third in income—as though most of this earlier debate had pretty much never taken place. This book, as noted above, was endorsed by presidents Clinton and Obama and received several prestigious awards. The Wikipedia summary of it (as of June 2020) highlights its chapter attacking What’s the Matter With Kansas as its most notable element.

3. Leading pundits weighed the evidence and rendered their verdict: Bartels was clearly correct. Between 2007 and 2015, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman used his vast authority among liberals to agree on several occasions that the shift of working-class people to the Republican Party was a myth and that it was not happening outside the South. He initially described this finding as arising from a collegial meeting of the minds between experts, with Krugman huddling with his “Princeton colleague Larry Bartels,” a political scientist who knew all about working-class voters and their undying—even growing!—loyalty to the Democratic Party.

It seems incredible from today’s vantage that anyone could have argued such a thing. But Krugman did, and repeatedly. Here are some examples: a blog post from 2007; a column in the Times in 2008 (“Nor have working-class voters trended Republican over time,” he wrote; “on the contrary, Democrats do better with these voters now than they did in the 1960s”); his book, Conscience of a Liberal, originally published in 2007 but reprinted in 2009 and 2015; and a Times column in 2015, in which Krugman was still insisting that “the working-class turn against Democrats wasn’t a national phenomenon — it was entirely restricted to the South.”

Krugman was probably the most highly regarded liberal columnist of that era, and it pleased him to note that his insights were derived from the lofty world of social science, not mere journalistic observation. Between his influential endorsement and that of two Democratic presidents, the Bartels Thesis was on its way to becoming the accepted wisdom of the age.

Other members of the punditburo arrived at the same conclusions. For example: Katrina Vanden Heuvel and my old pals at The Nation, who waxed enthusiastic about the Bartels Thesis on October 11, 2005; Matt Yglesias, who did the same in The American Prospect, February 2006, and Marc Ambinder in The Atlantic, April 14, 2008.

The appeal of the Bartels Thesis for partisan Democrats was easy to understand. The triumph of Republicanism, it seemed to suggest, had little to do with persuasion or with the defection of a core Democratic group. That was not happening; there was nothing to worry about. Furthermore, very little had changed over the years in the way ordinary Americans thought about politics, and therefore Democrats needed to do nothing differently, except perhaps to get tough and play the game a little better.

Also: the allure of academic expertise and math-based politics, which are never minor factors among professional-class liberals.

(NB: I originally pointed much of this out in a column for The Guardian in January, 2018.)

4. A handful of scholarly works appeared in those same years that refuted the Bartels Thesis and supported the general argument of Kansas either in part or as a whole. A sampling:

- A 2009 paper by David Brady and two other sociologists published in Social Science Research examined voting practices by occupation and confirmed that white working-class voters had indeed migrated toward the Republican Party in recent years. The authors wrote, “The White male working class has moved suddenly and massively towards the Republican Party since 1992. Our dating of this transition roughly coincides with Frank’s identification of the early 1990s as the point when the White working class began to dealign from the Democratic Party. In sharp contrast to Bartels, we contradict claims that the White working class shift towards Republicans is isolated to the South. Moreover, we demonstrate that his proxies for class are not adequate and that theoretically justifiable measures of class are essential.” Here is a PDF of the essay.

- Additionally, two of the sociologists wrote this summary of their findings (scroll down to page 10): “For social science to inform the public, it must use the best measures. Bartels, however, ignores the vast sociological literature on class voting. When we measure class validly, we uncover a good deal of support for the picture sketched by Thomas Frank in his 2004 book, What’s the Matter with Kansas, which described the desertion of the Democrats by the White working class. Although Bartels provides a reassuring story for Democrats, the reality is much closer to Frank’s Kansas.”

- A 2014 paper by two economists in the Journal of Law and Economics also examined how working-class voting practices had been changed by the rise of the culture wars and the migration of the Democratic Party to the right on economic issues. (Here is a summary on the LSE website.)

As far as I have been able to tell, these works made no impression at all.

5. The shocking election of Donald Trump in 2016, courtesy of the industrial states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin, finally put the Bartels Thesis to rest. The movement of the white working class towards the Republican Party was now undeniable, even to political scientists. Trump beat Hillary Clinton among non-college whites by a shattering 39 points. Again, a few instances give the unpleasant flavor of the moment.

- On November 9, 2016, Nate Cohn wrote for the New York Times website an essay entitled “Why Trump Won: Working-Class Whites.” “[T]he bastions of industrial-era Democratic strength among white working-class voters fell to Mr. Trump,” Cohn noted. “So did many of the areas where Mr. Obama fared best in 2008 and 2012. In the end, the linchpin of Mr. Obama’s winning coalition broke hard to the Republicans.”

- Jim Tankersley, blogging on the Washington Post website on the same day, wrote a piece called “How Trump Won: The Revenge of Working-Class Whites.” Speaking of “blue-collar white men,” Tankersley wrote that “On Tuesday, their frustrations helped elect Donald Trump, the first major-party nominee of the modern era to speak directly and relentlessly to their economic and cultural fears. It was a ‘Brexit’ moment in America, a revolt of working-class whites who felt stung by globalization and uneasy in a diversifying country where their political power had seemed to be diminishing.”

- NPR’s story on the election results, published on November 12, 2016, described “Democrats’ cratering with blue-collar white voters” as “what might be the biggest story of the election.” NPR further pointed out that the last time a Democratic presidential candidate prevailed among this cohort was in 1996.

Eventually this narrative would change. Before long, “white working class” would become a phrase denoting racist authoritarianism, while Trump’s election would be written off to various forms of irrationality. But we will leave those controversies for another day. The subject here is the fate of the original Bartels Thesis—that white working class voters in northern states remained loyal Democrats. To put it briefly, the argument did not age well. A paragraph from The Wall Street Journal’s survey after the election of 2020 gives a taste of the new view among political observers:

“Since the Reagan era, the two parties have essentially traded their core supporters. Democrats, the party of union halls and working-class America, now include much of the nation’s professional class. Republicans, once the party of Americans with four-year college degrees, are increasingly the party of the white working-class—and, the 2020 election showed, of a larger minority of Hispanic Americans.”

This is, in essence, the thesis of What’s the Matter With Kansas?.

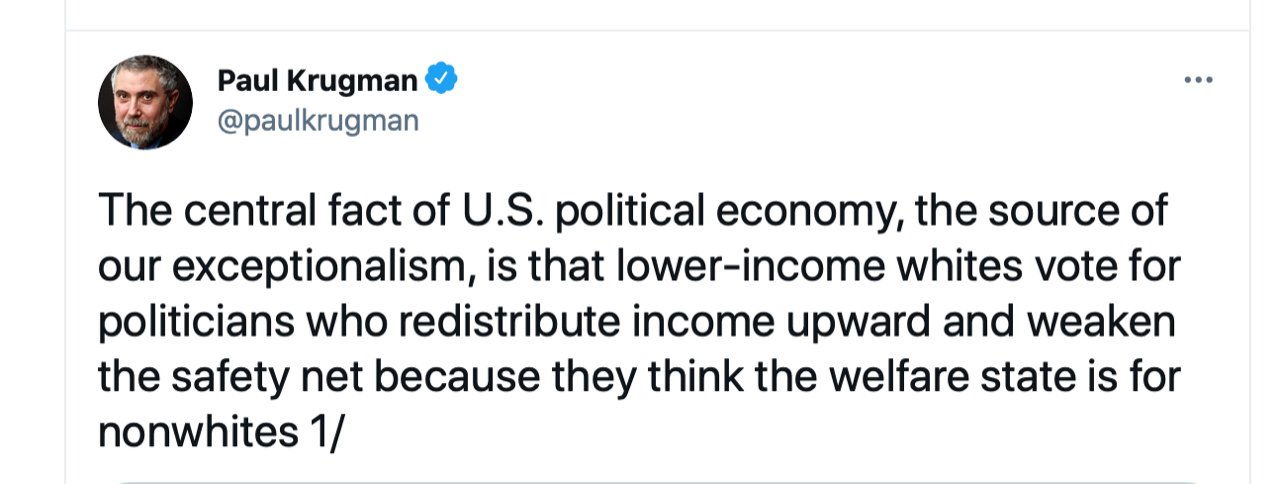

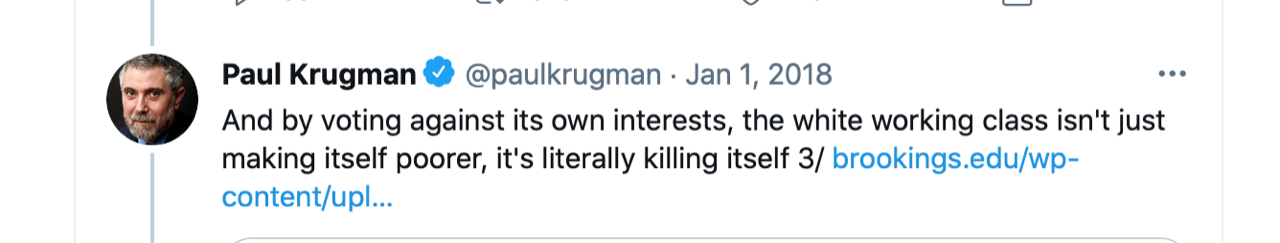

5 (a). What about Paul Krugman and the rest of the punditburo? One year into the Trump Administration, the nation’s leading economist/columnist tweeted as follows:

and then this:

Quite a reversal! But on the essential question of What to Do About It?, Krugman remained steadfast. Virtually nothing could to be done to win those voters back! Reviewing a 2020 book by economist Thomas Piketty, Krugman noted Piketty’s suggestion that left parties reach out to working-class voters with “populist economic policies” and then dismissed it:

Piketty could be right about this, but as far as I can tell, most political scientists [!] would disagree. In the United States, at least, they stress the importance of race and social issues in driving the white working class away from Democrats, and doubt that a renewed focus on equality would bring those voters back.

The expertise of the same old experts was deployed to steer us to the same old conclusion: that nothing could be done, therefore nothing needed to be done. La plus ça change . . .

(Similarly, Marc Ambinder wrote a column in 2016 scolding “the media” for missing the “white wave” that elected Trump—and also sneering at “the pundit herd” for caring about the “working-class white vote.” The following year Katrina Vanden Heuvel saw fit to write a column titled “How Democrats can win back the working class.”)

6. Speaking of Thomas Piketty: In 2018 and without referring to my dispute with Bartels, Piketty published a famous paper that used the same ANES data that Bartels and I argued about in 2005 . . . to make exactly the opposite point from Bartels. As Piketty put it, the Democratic Party had transitioned “from the worker party to the high education party.” (See in particular his Figure 3.3a and 3.3c.) This shift, Piketty pointed out, had taken place gradually over many years but became markedly more pronounced in 2016, when Democrats finally won outright the vote of the upper 10%. Piketty’s findings were later incorporated into his 2020 book, Capital and Ideology, the one Krugman reviewed so uncharitably in the item above.

7. Coda. Larry Bartels went on to occupy a named chair at Vanderbilt University, from which seat he has collected countless honors and awards. In 2016, Bartels’s prize-winning and president-approved book, Unequal Democracy, was reissued in a second edition. However, the chapter of Bartels’s book having to do with What’s the Matter With Kansas?—the element of the book that was widely regarded as its most important intervention—was omitted from the new edition.

And me? I learned a valuable lesson in cultural legitimacy and what happens to those who don’t possess it. With that knowledge I went on to write a series of books about how liberals became more interested in professional expertise than in the fate of working people. But that’s a story for another occasion.